As Cortes moved closer to the Mexica capital of Tenochtitlan, he passed through Cholula. This town of about 30,000 (de las Casas) was a sort of religious capital in the region, comparable to Mecca or Jerusalem. The people of Cholula were allied with Moctezuma and were enemies of Tlaxcala where Cortes had been received. The Spanish account paints Cortes in a desperate situation, pinned in an enemy city and reacting defensively. Other accounts, both indigenous and European, tend to call it a massacre.

The Cortes Narrative

After brief negotiations that Cortes felt were short of his esteem, he marched on Cholula with 1,000 Tlaxcala warriors (Cortes, 2nd Letter). Cortes was met with much fanfare and was admitted to Cholula. According to Spanish accounts and those of the Tlaxcala storytellers, Moctezuma and the leaders of Cholula had cooked up a scheme to trap the Spanish in the city and destroy them. Cortes’s Cempoalan allies noted trenches dug, and rock piles on rooftops and they reportedly saw women and children being led out of the city. In another account La Malinche, the indigenous female translator, was approached by a Tlaxcala woman who, in an offer of sanctuary, confided in her the plot to kill the Spanish.

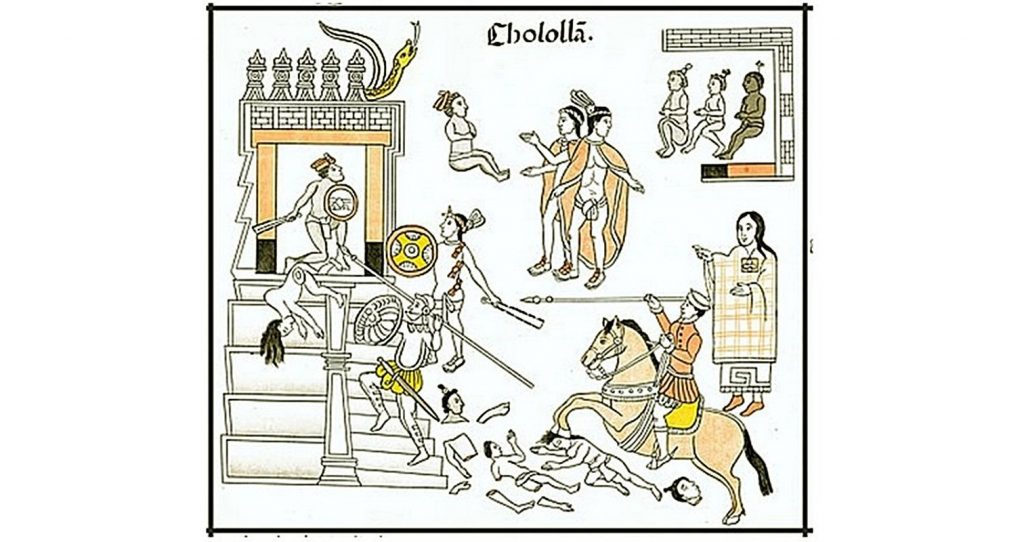

Convinced of the oncoming assault, Cortes called a meeting of all the men of matter in the Cholula region. Once they had gathered he explained their treachery to them and ordered a musket fired. This was the sign for the Spanish and their allies to begin the assault on the Cholulans. Cortes claims 3,000 were killed in a two-hour slaughter.

Cortes and Diaz explain it was a natural pre-emptive strike against an obviously hostile force. The Tlaxcala stories also justify their actions, including the mutilation and murder of one of their messengers before the attack. It seems a logical place for Moctezuma’s allies to make a stand if you were going to try and expel these invaders once and for all.

The majority of the Tlaxcala army had waited outside the city and once the battle had begun entered Cholula. The Tlaxcala force fought through the streets toward the Spanish, who had already begun slaughtering people. For almost two days the Tlaxcala army pillaged and burned Cholula until even Cortes was taken by pity for the people of Cholula. He ordered the pillaging to end and demanded all the captives taken by the Tlaxcalans be returned.

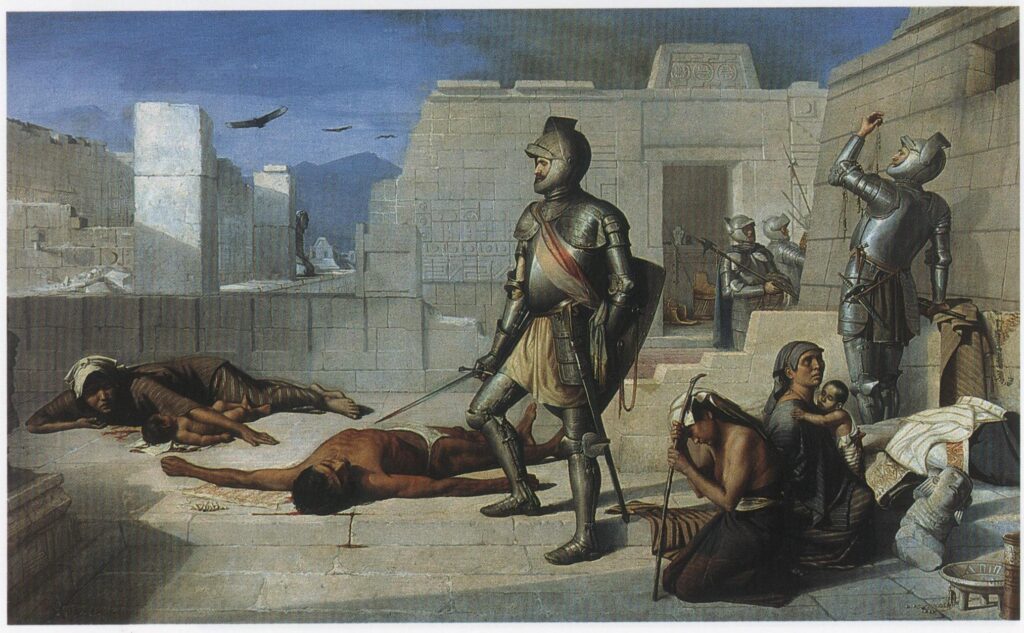

Cortes was a cunning and brutal leader and he either anticipated the attack or simply intended to send a brutal message. And it seems to have worked as word spread far and wide of the destruction of the Cholula nobility by the invaders.

Other Accounts

Other accounts are not so clear on a sneak attack by the Cholulans and refer to it as an outright massacre. The Conquistador turned Mercedarian friar Francisco de Aguilar said the people killed were water-bearers and temames. Diego Duran also noted they were bringing supplies and highlights the incident as a dark point he must write about. The historian and early civil rights advocate Bartolome de las Casas called it a staged “massacre” and a “punishment” by Cortes to spread terror. Las Casas also said it was mostly temames, the most humble and respected worker in Mesoamerica, who made up the bulk of the victims.

The Florentine Codex describes the massacre as planned by the Spanish, but notes there was no Cholulan scheme, saying they were unarmed and were “treacherously and deceitfully slain.”

Within a few days the Spanish had moved out of Cholula toward Tenochtitlan, news of their terror well ahead of them. Cortes ordered the people of Cholula to resume their lives as before. Which they did, but forever tainted by the destruction brought by the Spanish.

Estimates from various accounts range from 2000 to 6000 victims with not a single Spanish casualty.