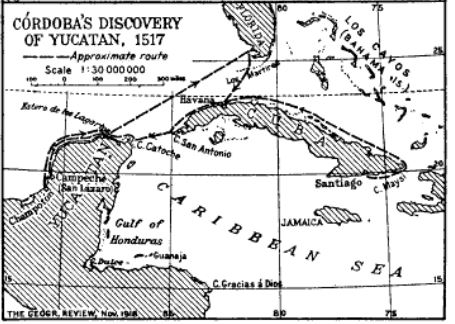

The first expedition to Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula was led by Francisco Hernandez de Cordoba. He and 110 men on three vessels departed Cuba on February 9, 1517 and within weeks had spotted pyramids, people and farms in places like Isla de Mujeres and El Meco. There is some debate as to what and where Cordoba saw, but it seems they came in at Isla de Mujeres and from there possibly spotted the pyramids at El Meco, which they dubbed “El Gran Cairo” or the Great Cairo for its resemblance to Egypt.

The expedition moved on North, toward a place where they would come to call Cape Catoche. Here they were met by 10 large canoes, according to Bernal Diaz. After some friendly gesturing, as there were no Maya-Spanish translators yet, they had 30 men aboard the ship. The Spanish gave them beads. The Maya men left but indicated they’d be back tomorrow.

On March 5, 1517, 12 canoes arrived and beckoned the Spanish to come ashore with promise of food and water. Cordoba agreed it seemed a decent wager and took his men ashore. The apparent Maya leader led the Spanish inland, friendly all the time, Diaz claims.

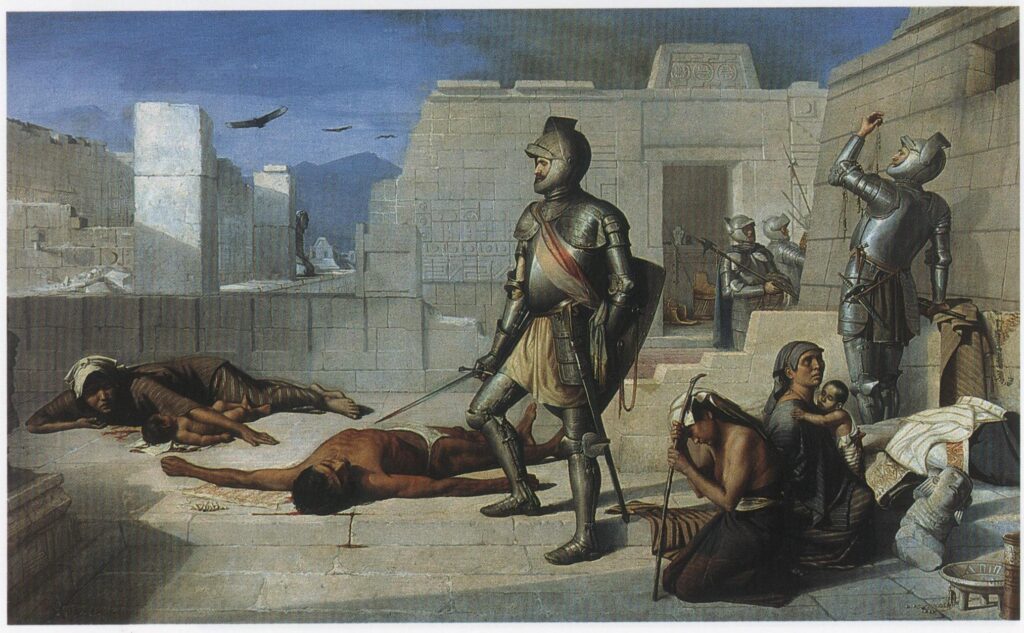

With a loud shout the Maya leader ordered a heavy projectile attack on the Spanish and a cloud of arrows, spears and stones assaulted them, wounding 13, according to Diaz. As the Maya warriors advanced for hand to hand the Spanish technological advantage became clear as their swords slashed at the Maya, claiming 15 lives.

The Spanish were able to fight their way back to the boats and make it to the ships out at sea. Within days two men would succumb to their injuries and were buried at sea. The Spanish seized some low quality gold and captured two Maya men. One of the men, baptized as Melchior, would become a translator for the Cortes Expedition.

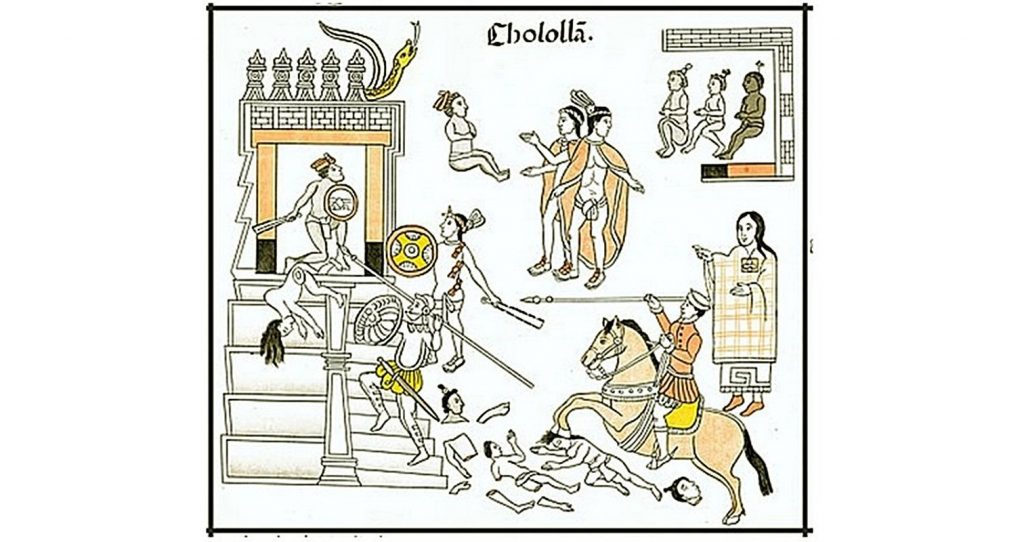

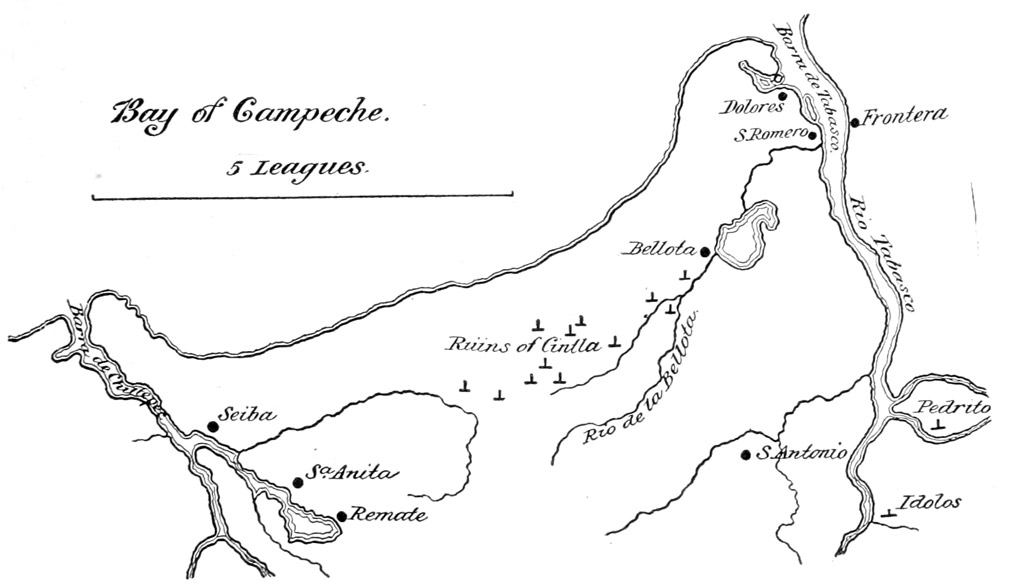

The Expedition moved East along the coast until they reached Campeche. Exhausted and feeling the effect of severe dehydration the men put ashore with their leaky casks. Here they were greeted by 50 people and invited to town. It was here the Spanish saw human sacrifice for the first time. Dreadlocked priests covered with knotted blood came out and waved incense over the Spaniards. The increasing agitation of the crowd soon made clear the Spanish needed to leave. Fearing another attack they did so.

Battle at Chompoton

Days later the Spanish saw a town and, driven by thirst, unloaded the casks again and began to fill them at a maize farm. Soon hordes of warriors began to appear and surround them. But the Maya warriors departed at nightfall.

The pre-dawn hours brought the distant noise of rallying warriors, drums and shouting. The warriors would soon be upon them. The dawn light brought a terrible sight for the Spanish as Maya divisions were lining up along the coast, behind them, on all sides. And more warriors were pouring in.

First the arrows and stones poured in wounding up to 80 of 108 men, according to Diaz. Next came the hand to hand combat with the two handed wood and obsidian swords of the Maya against Spanish steel blades. Despite their arms advantage, more than 50 Spaniards were killed in the battle and the men were driven to their boats, the remaining men barely escaping with their lives.

In the end the battle lasted one hour, two Spaniards were captured alive, 50 men were killed on the battlefield; every soldier, Diaz says, received multiple arrow wounds. Five more men would succumb to their wounds in the following days.

Following the calamitous battle, the men decided to head for Cuba but had to scuttle one ship due to a shortage of men to sail. They sailed along the coast for awhile looking for water, eventually crossed the Gulf of Mexico to Florida where they found life-saving water, had another skirmish with Indigenous warriors there before making back to Cuba.

Cordoba would soon die of his wounds in Cuba. Besides Bernal Diaz, several other men from the Cordoba Expedition would go on to participate in the Grijalva and Cortes Expeditions, including the pilot Anton de Alaminos, Juan Alvarez “El Manquillo,” and a priest named Alonso Gonzalez.