Below are lists and descriptions of the Great Treasure presented to Cortes in San Juan de Ulua. This is the legendary gift presented by Tendile and includes the much mentioned gold sun-disc and silver moon-disc. The descriptions of the treasure and the place vary by writer, but most place the exchange on either Cortes’s flagship or the beach where his men were setting up camp.

Florentine Codex – Moctezuma sends five leaders to greet Cortés, who he believes to be Quetzalcoatl and to take the gifts he had made when Grijalva was spotted off the coast. These things were carried from Tenochtitlan to the coast and presented to Cortés.

- Turquoise Mask – snake design, inlaid turquoise with a crown of rich long plumes. It also had a crown and a chest piece attached that covered the chest and shoulders.

- Shield – beaded and jewelled shield, round shape.

- Anklet, strings of precious stones with Golden Bells

- Scepter covered with turquoise snake design

- Headpiece, shell shaped, of gold.

- Accoutrements of Tezcatlipoca

- Headpiece of rich plumes with golden stars

- Gold ear plugs with attached sea shell chest plate

- Corselet of white cloth, painted cloth with feather bands

- Cloak, light blue, “tzitzilli”

- Sandals of lords

- Accoutrements of Tlalocan teuctli –

- Mask with plumage and chest piece

- Ear plugs

- Coreselet of green cloth

- Medallions

- Staff

- Anklets

- Serpent staff of turquoise

- Quetzalcoatl’s Belongings

- Jaguar skin miter (headpiece) with pheasant feathers

- Turquoise ear plugs

- Gold necklace with medallion

- Shield, round with gold plate in center, rich feathers on the edge

- Cloak

- Anklet bells

- Staff encrusted with pearls

- Sandals of the lords

- Gold miter with rich plumes

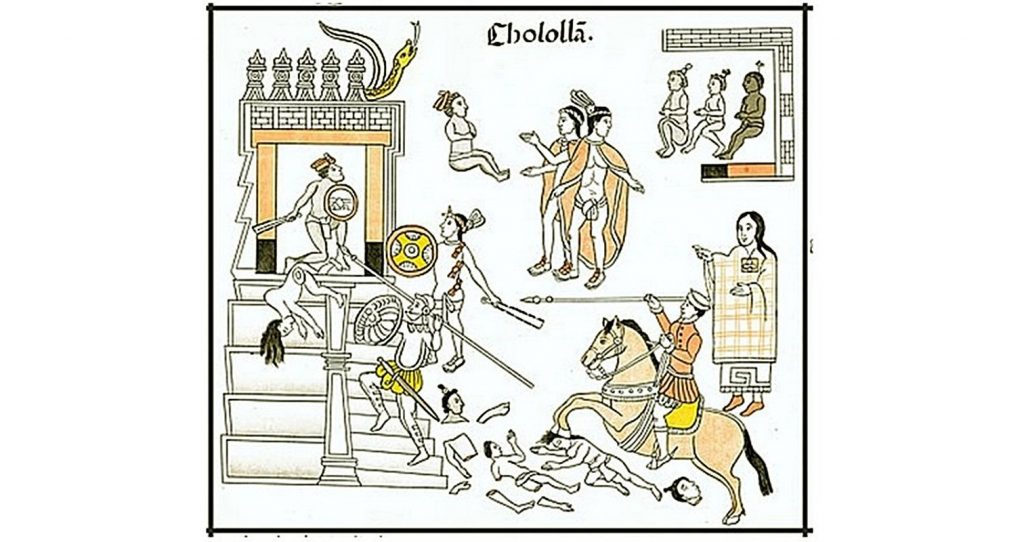

Annal of Tlatelolco – Very basic narrative, tells that they met Cortes at Tecpantlayacac and gave him the listed gifts. Also that a sacrifice was performed and rebuked with punishment of death by Cortes.

- Suns of yellow and of white (gold and silver)

- Mirror

- Golden helmet

- Golden shell headcover

- Head fan of plumes

- Shield of shell

Annals of Quauhtitlan – Briefly describes the coastal contacts and mentions gifts sent to Moctezuma as well.

- Green frock

- Two capes,red and a black

- “Two pairs footwear, shoes”

- A knife

- A hat; cap

- A woolen cloth

- A Cup

- beads

Andres de Tapia – In his Relacion, deTapia mentions gifts of gold and silver including the discs. He then describes the robes, necklaces and beads Cortes sends to Moctezuma.

- “present of gold and silver, and in it a wheel of gold and another of silver, each one as large as a cartwheel, though not very thick, which say they are made in the likeness of the sun and the moon.”

Diaz – San Juan de Ulua, (Diaz 93) – Gives a very brief description of the treasure presented initially by Tendille (meager gold and food). A week later he presents the grander treasure.

- Gold Sun-disc, as big as a cartwheel, worth 10K pesos

- Silver Moon-disc

- Helmet full of gold granules (as requested by Cortes), worth more than 3K pesos

- 20 golden ducks and other golden animals

- Bow and 12 arrows

- Golden staffs (two)

- Gold crests

- Fans and plumes of green featherwork

- Silver crest

- 30 loads of cotton, decorated with feathers.

Gomara – Camp at San Juan de Ulua (Gom 59) – Presented by Teudilli at the Ulua camp.

- Many mantles and garments

- Many plumes

- Many gold objects

- Jewels and gold and silver pieces

- Gold sun-disc, weighs 52 marks, worth 20,000 ducats

- Silver moon-disc, weighs 100 marks

Cortes “First” Letter (Cort 74) – Briefly mentions several gifts over a period of time. There is a list of the gifts provided.

- Gold wheel representing the sun.

- Silver wheel representing the moon.

- 2 Gold necklaces with inlaid rubies, emerald, pearls.

- Headdress withhold and plumes.

- Skins,leather shoes with gold trim.

- 24 gold shields with feathers and jewels.

- Animals made of gold.

- Several fans.

- Large mirror

- Cotton robes

- Tapestries and blankets