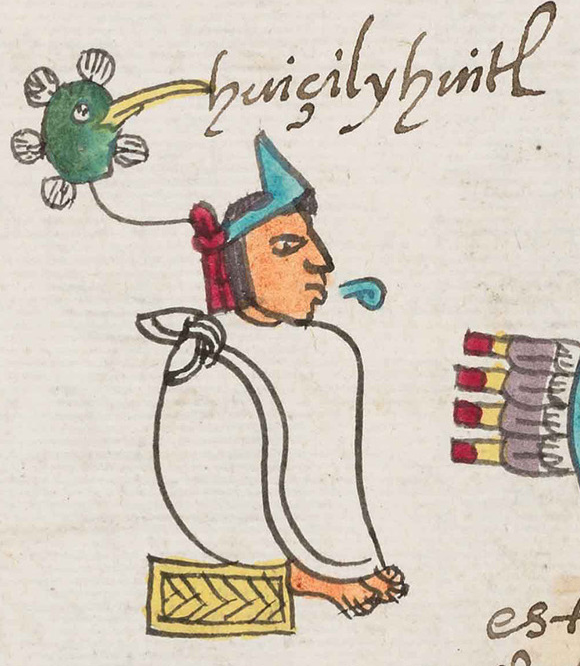

Formal Name: Huitzilihuitzin

Life: Unknown-1416

Reign: 1396-1416

Name: hummingbird feather

Place of Birth: likely Tenochtitlan

Died: Likely in Tenochtitlan of natural causes.

The second Tlatoani of Tenochtitlan, and the first that was born in the city, was Huitzilihuitl or formally known as Huitzilihuitzin. He was the son of the first tlatoani, Acampichtli, and a Mexica mother named Tezcatlan Miyahuatzin. His name translates to hummingbird feather, and his name glyph is shown as a green hummingbird head with feathers on the sides. The hummingbird was an important spiritual animal to the Mexica and their feathers were valued more than precious metals.

Huitzilihuitl was born into a growing Mexica community still subject to the Tepanec people of Azcapotzalco and their king Tezozomoc. Before he died, Acampachtli established the calpultin, a council of the four districts, that would not only consider nobility, but ability of potential rulers. Huitzilihuitl was the first selected by this council for his kindness and peaceable manner, according to Duran. The Cronica Mexicayotl describes him as a “very beloved son.”

A quick historic note, there was an earlier Mexica ruler named Huehue Huitzilihuitl, who ruled before the Mexica had settled in Tenochtitlan and were still living in Chapultepec. These are two separate men, who ruled at different times and in different capacities. Huehue Huitzilihuitl was captured and executed by the rulers of Culhuacan. It was almost a hundred years later that Tlatoani Huitzilihuitl reigned in Tenochtitlan.

Huitzilihuitzin took the throne at about age 16, after the death of his father circa 1403. Militarily, he continued to ally the Mexica with Tezozomoc in Azcapotzalco in their feud with Texcoco. During his reign he took several wives from other altepetls with an eye toward bolstering the Mexica nobility, including noblewomen from their Tepenec rulers in the cities of Tlacopan and Azcapotzalco. His political positioning was so important that a group of Mexica nobles went to Tezozomoc and asked for a daughter to marry Huitzilihuitl. Tezozomoc agreed, providing his daughter Ayauhuacihuatl to marry the Mexica king.

The new queen immediately went to work advocating for her new people to her father Tezozomoc. And Tenochtitlan profited greatly from her efforts, receiving gifts and reduced tribute levels. The queen also bore a son. When word was sent to Tezozomoc in Azcapotzalco, he was overjoyed and had his priests pray on a name. They returned with the name Chimalpopoca. The name was received in Tenochtitlan and given to the new prince. The baby would grow to become a favorite of his powerful grandfather.

Huitzilihuitl pursued his father’s politics, building ties to Azcapotzalco, slowly strengthening the city and army but like his father he did not break free from Tepanec control, but through marriage he loosened its grip. His reign saw the spread of cotton weaving, elevating Mexica clothing from the coarser maguey (agave) fabrics to the much softer cotton fabrics. Additionally he built schools, temples and renovated the Templo Mayor. He also was known to have issued laws to codify Mexica society. His legacy would continue through his sons, including two future tlatoque, Chimalpopoca and Moctezuma Ilhuicamina, as well as the powerful warrior, advisor and shaper of Mexica politics and culture, Tlacaelel.

The Florentine Codex summarized his reign like this: Vitsivitl, was the second lord of Tenochtitlan: the one who had dominion. Twenty and one years: and he began the wars, and fought with those of Culhuacan.

When the Queen Ayauhuacihuatl died it left the Mexica people heartbroken as she had taken them into her heart and was their protectress. A year later Huitzilihuitl also died around 1417, much beloved for his growth of the city. His son Chimalpopoca, the favored grandson of Tezozomoc, would succeed him.

Huitzilihuitzin’s Accomplishments

Supported Azcapotzalco in their war with Texcoco.

Cotton clothing adopted during his reign.

Codified early laws.

Acamapichtli <<- Huitzilihuitl ->> Chimalpopca