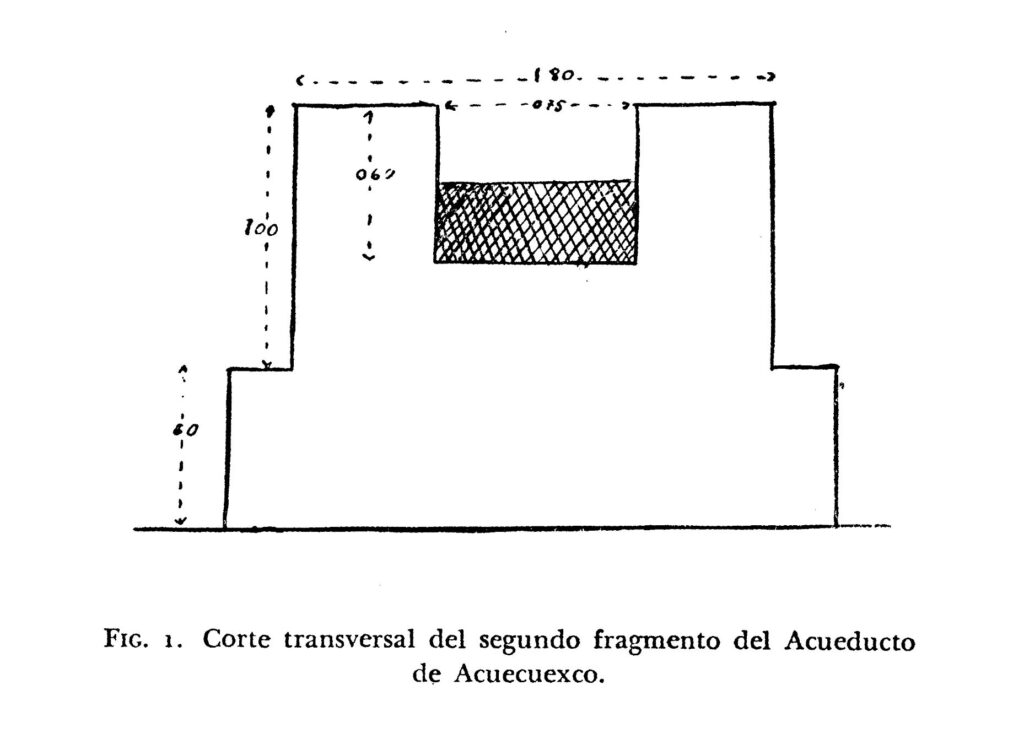

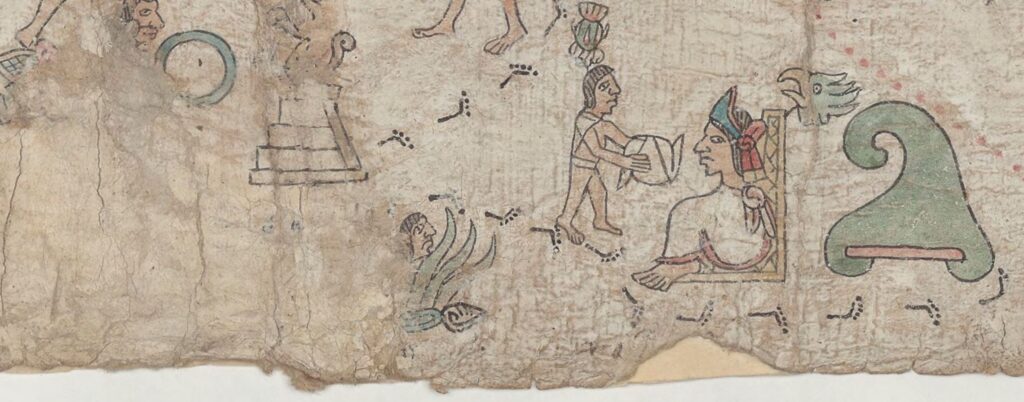

In the Churubusco neighborhood of Coyoacan there were a number of springs that watered the indigenous communities there. Tenochtitlan’s Tlatoani Ahuitzotl, in a desire to feed his growing city, asked to use the water from Coyoacan, and the Acuecuexco spring, among others. Tzutzuman, ruler of Coyoacan, advised against an aqueduct into the city, that it might cause a flood, according to Duran. Whether it was unwanted advice or just the refusal to grant permission to the water, it’s not totally clear, but it seems Ahuitzotl had Tzutzuman killed.